Moore’s Law is the famous prognostication by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore that the number of transistors on a microchip would double every year or two. This prediction has mostly been met or exceeded since the 1970s — computing power doubles about every two years, while better and faster microchips become less expensive.

This rapid growth in computing power has fueled innovation for decades, yet in the early 21st century researchers began to sound alarm bells that Moore’s Law was slowing down. With standard silicon technology, there are physical limits to how small transistors can get and how many can be squeezed onto an affordable microchip.

Neil Thompson, an MIT research scientist at the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and the Sloan School of Management, and his research team set out to quantify the importance of more powerful computers for improving outcomes across society. In a new working paper, they analyzed five areas where computation is critical, including weather forecasting, oil exploration, and protein folding (important for drug discovery). The working paper is co-authored by research assistants Gabriel F. Manso and Shuning Ge.

They found that between 49 and 94 percent of improvements in these areas can be explained by computing power. For instance, in weather forecasting, increasing computer power by a factor of 10 improves three-day-ahead predictions by one-third of a degree.

But computer progress is slowing, which could have far-reaching impacts across the economy and society. Thompson spoke with MIT News about this research and the implications of the end of Moore’s Law.

Q: How did you approach this analysis and quantify the impact computing has had on different domains?

A: Quantifying the impact of computing on real outcomes is tricky. The most common way to look at computing power, and IT progress more generally, is to study how much companies are spending on it, and look at how that correlates to outcomes. But spending is a tough measure to use because it only partially reflects the value of the computing power being purchased. For example, today’s computer chip may cost the same amount as last year’s, but it is also much more powerful. Economists do try to adjust for that quality change, but it is hard to get your hands around exactly what that number should be. For our project, we measured the computing power more directly — for instance, by looking at capabilities of the systems used when protein folding was done for the first time using deep learning. By looking directly at capabilities, we are able to get more precise measurements and thus get better estimates of how computing power influences performance.

Q: How are more powerful computers enabling improvements in weather forecasting, oil exploration, and protein folding?

A: The short answer is that increases in computing power have had an enormous effect on these areas. With weather prediction, we found that there has been a trillionfold increase in the amount of computing power used for these models. That puts into perspective how much computing power has increased, and also how we have harnessed it. This is not someone just taking an old program and putting it on a faster computer; instead users must constantly redesign their algorithms to take advantage of 10 or 100 times more computer power. There is still a lot of human ingenuity that has to go into improving performance, but what our results show is that much of that ingenuity is focused on how to harness ever-more-powerful computing engines.

Oil exploration is an interesting case because it gets harder over time as the easy wells are drilled, so what is left is more difficult. Oil companies fight that trend with some of the biggest supercomputers in the world, using them to interpret seismic data and map the subsurface geology. This helps them to do a better job of drilling in exactly the right place.

Using computing to do better protein folding has been a longstanding goal because it is crucial for understanding the three-dimensional shapes of these molecules, which in turn determines how they interact with other molecules. In recent years, the AlphaFold systems have made remarkable breakthroughs in this area. What our analysis shows is that these improvements are well-predicted by the massive increases in computing power they use.

Q: What were some of the biggest challenges of conducting this analysis?

A: When one is looking at two trends that are growing over time, in this case performance and computing power, one of the most important challenges is disentangling what of the relationship between them is causation and what is actually just correlation. We can answer that question, partially, because in the areas we studied companies are investing huge amounts of money, so they are doing a lot of testing. In weather modeling, for instance, they are not just spending tens of millions of dollars on new machines and then hoping they work. They do an evaluation and find that running a model for twice as long does improve performance. Then they buy a system that is powerful enough to do that calculation in a shorter time so they can use it operationally. That gives us a lot of confidence. But there are also other ways that we can see the causality. For example, we see that there were a number of big jumps in the computing power used by NOAA (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) for weather prediction. And, when they purchased a bigger computer and it got installed all at once, performance really jumps.

Q: Would these advancements have been possible without exponential increases in computing power?

A: That is a tricky question because there are a lot of different inputs: human capital, traditional capital, and also computing power. All three are changing over time. One might say, if you have a trillionfold increase in computing power, surely that has the biggest effect. And that’s a good intuition, but you also have to account for diminishing marginal returns. For example, if you go from not having a computer to having one computer, that is a huge change. But if you go from having 100 computers to having 101, that extra one doesn’t provide nearly as much gain. So there are two competing forces — big increases in computing on one side but decreasing marginal benefits on the other side. Our research shows that, even though we already have tons of computing power, it is getting bigger so fast that it explains a lot of the performance improvement in these areas.

Q: What are the implications that come from Moore’s Law slowing down?

A: The implications are quite worrisome. As computing improves, it powers better weather prediction and the other areas we studied, but it also improves countless other areas we didn’t measure but that are nevertheless critical parts of our economy and society. If that engine of improvement slows down, it means that all those follow-on effects also slow down.

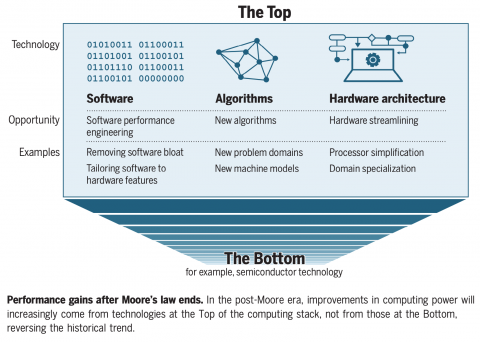

Some might disagree, arguing that there are lots of ways of innovating — if one pathway slows down, other ones will compensate. At some level that is true. For example, we are already seeing increased interest in designing specialized computer chips as a way to compensate for the end of Moore’s Law. But the problem is the magnitude of these effects. The gains from Moore’s Law were so large that, in many application areas, other sources of innovation will not be able to compensate.